Being Aware of Visible (and Invisible) Surveillance at Protests

Victoria Police has an arsenal of surveillance equipment and tactics that are regularly deployed against activists. In some cases, new equipment or tactics are trialled at simple demonstrations or marches for use in more rigorous situations later, such as direct actions or protest events. Other times, police surveillance has become a normalised part of life in modern society.

Being aware of some of the visible and invisible surveillance that police particularly use against activists is a part of being able to endure in your activism, and is an important part of cultivating and sustaining a culture of resistance as a whole.

Surveillance that May be Visible

Evidence Gathering Teams

‘Evidence Gathering Teams’ is a euphemism for targeted surveillance of individual activists by police, as well as general surveillance of activist movements as a whole. They typically consist of teams of officers that are equipped with long-range video recording equipment that can live-stream videos back to central command, and/or record the video footage for analysis and profiling later. Evidence Gathering Teams are usually part of the Public Order Response Team, although other officers can and do undertake surveillance and recording roles.

Victoria Police have stated as recently as 2012, that footage from Evidence Gathering Teams may be kept for up to 50 years.1

Surveillance teams like this can sometimes come up close to activists and get right in their face, while other times they stand back and monitor from afar. Sometimes they also attempt to ‘hide’ or obscure their presence by standing behind pillars or recording from inside police cars. While this can be intimidating, and the police do use Evidence Gathering Teams precisely for this reason, this shouldn’t deter activists and movements in general from challenging the pervasive surveillance they face; and challenging the chilling-effect surveillance can have on political expression, and the simple exercising of civil and political rights.

Body-Worn Cameras

Perhaps some of the most close and direct surveillance that police undertake in terms of physical proximity, as part of duties of all kinds, is video and sound recording from body-worn cameras. These are the square boxes usually mounted on the front of a police officer’s chest, courtesy of a multi-million dollar deal with Axon corporation and its evidence.com cloud solution2–the same corporation that supplies cameras and evidence storage to police officers throughout the United States.3

These video cameras are not always recording, as it’s up to the individual officer to turn them on.

Police also have the power to tamper with footage from these cameras after an event (making edits and modifications as they see fit),4 and also to exclude the footage from Freedom of Information Act requests.5 The police may use such footage from body-worn cameras in court as part of claims against citizens, but inversely, citizens cannot access nor use the footage in court as part of claims against the police.6

Drones and Helicopters

Drones, or ‘Unmanned Aerial Vehicles’ are devices that can be equipped with high definition, live-streaming video cameras; thermal-infrared video cameras; heat sensors; and radar devices—all of which allow for sophisticated and persistent surveillance from a distance. Drones can capture and record video in daylight, or use infrared technology to capture video and images at night. They can also be equipped with other capabilities, such as mobile-phone interception technology, or Automated Number Plate Recognition, for example.

Drones vary in size, from tiny quadrotors weighing only a few kilos, all the way up to large fixed aircraft the size of small passenger planes.

Drones are harder to spot than helicopter surveillance, because they are smaller and quieter, may be deployed at higher altitudes, and they can sometimes stay in the sky for days at a time. Victoria Police use drones for crowd control, and have a special Drones Unit specifically for this purpose.7 Activists and journalists may also deploy drones in a protest setting however, exercising their rights to gather information about police response or the protest event itself. So if you do see a drone at an event, you should not automatically conclude that it belongs to the police.

Police helicopter surveillance may be deployed at protest events, as part of the Air Wing. Police helicopters are full of advanced surveillance equipment, such as high definition zoom cameras, night vision, traffic monitoring and number plate recognition capability, automatic target tracking, and other covert surveillance and observation tools.8 Their use in monitoring large protests is usually ubiquitous and obvious. But likewise with drones, mainstream media also use helicopters to capture news footage, so you should not automatically conclude that all helicopters are targeted police surveillance.

Automated Number Plate Recognition

Automated Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) systems are computer-controlled cameras that rapidly capture images of license plate numbers; along with the location, date, and time; which is then used to extract and compare information from databases automatically, such as the owner’s name and address of a particular vehicle.

These image recognition systems can operate in both mobile and stationary modes. For example, Victoria Sheriffs are known to conduct mobile operations at locations such as carparks by mounting ANPRs to the exterior of their vehicles and mass-reading number plates as they travel past.9 The technology can also be set up in a fixed position and used at roadblocks, or to monitor specific areas. Police use ANPR heavily in highway patrols, and many highway patrol vehicles in Melbourne have ANPRs attached to them, courtesy of Motorola Corporation.10

At a protest, police may deploy ANPRs to identify people driving toward, away from, or parking near a march, demonstration, or other public gathering. Then, used in conjunction with other mobile or stationary ANPRs that may be located around the city, police have the capability to track activists as they travel from specific events back to their homes.

Mobile Surveillance Vehicles/Trailers

The City of Melbourne has a lucrative contract with Securecorp so that the city is covered in high definition CCTV cameras as part of the mass surveillance programme “Safe City Cameras.” You may notice such CCTV cameras on most major street intersections, strapped to traffic lights and street signs.

Securecorp also has a fleet of mobile surveillance vehicles, which are fitted with 360-degree CCTV surveillance cameras, that generally patrol the city on Friday and Saturday nights from 10pm to 6am, “all year round.”11

Sometimes Securecorp vehicles turn up to protest events especially and begin monitoring activists, and then provide that footage to the police, acting as a private security firm.

Private security firms like this are known to be hired by corporations or governments to covertly monitor activist movements, but Securecorp is notable in Melbourne because it is normalised by government contract, and is highly visible.

Even though police accountability is lax in Australia, private security firms are much less accountable in terms of surveillance, because they are corporate entities, and hence not as subject to oversight by the public. Indeed, because the Victorian Government has outsourced such a programme, even the precise commercial nature of contracts between corporations and government are largely exempt from public scrutiny.12

Surveillance that May Not be (as) Visible

Facial Recognition Software (or other Video Analytics)

Facial Recognition is a method of identifying or verifying a record of identity of an individual person by using a photograph of their face. This can take place from a still photograph, or can happen in real time from video feeds.

Facial recognition capability is becoming commonplace with many cameras and devices. At a protest, it may be reasonable to assume that any camera you encounter may have facial recognition or other video analytical capability, especially after-the-fact. This would include body-worn cameras, mounted cameras on buildings, streetlights, police vehicles, or surveillance towers.

What Victoria Police are doing with facial recognition technology is extremely unclear. Earlier this month, it was revealed that Victoria Police were using the services of the controversial facial recognition company Clearview AI,13 despite their previously repeated denials.14 Clearview AI, a company that has foundational links to neo-nazis and other far-right figureheads in the United States,15 describes itself as “Google for faces,” and it is known that Victoria Police officers were using the service as recently as March this year.16 However, when asked about this, Victoria police said that “only a small number of email addresses were registered [with Clearview AI], it was not used in any investigations, and police had discontinued using the service.” This is in contrast to a statement made earlier this year that “Victoria Police does use some facial recognition technology for investigative and intelligence gathering purposes, but does not comment on the specifics for security reasons.”17

Social Media Monitoring

Pervasive surveillance of activists and activist movements is made easy with ‘social media’ websites. This is because the information capable of being gathered or discerned from places like Facebook or Twitter is rich, finely detailed, is usually very accurate in terms of metadata and content, and is also very cheap to extract, given that you’ve essentially gifted all of this to the police for free. The digital trails generated from using social media websites, makes intelligence gathering and preemption extremely easy for the police, which is why they rely on it heavily to plan their responses to activist movements.

Police often scour hashtags, gather information about public events and activist discussions, but perhaps most importantly, make note of who you’re organising with, what your groups are, and what you’re planning. They can then use this information to operationally disrupt protest actions, intimidate individual activists, preemptively arrest or detain persons of interest, or round up activists after an event for arrest or other repressive actions such as ‘sting’ interviews.

Surveillance of social media is done by a mix of human police teams and also algorithms that collect and analyse social media posts that contain certain sentiments or keywords and phrases, geolocation tags, or connections to certain individuals or groups of interest, for example.

Social media corporations have been known to easily facilitate police intelligence gathering in this manner, offering detailed and sustained access to the data on their systems, sometimes with very low legal threshold,18 or in some cases, even just filling out a simple online form asking for access.19

There are also specialist private intelligence companies in Melbourne that are devoted to social media surveillance. For example, the National Open Source Intelligence Centre, or NOSIC, “works under contract for the Australian Federal Police and Federal Attorney-General’s Department to monitor activist websites, blogs, Facebook and Twitter to provide warning and analysis of protest activity.”20 The convergence of private intelligence gathering and police surveillance with the power of social media companies, means that digital repression of activist movements is both lucrative and pervasive.

As with Evidence Gathering Teams above, digital surveillance like this can sometimes be carried out very openly, and used as a tool of intimidation,21 but often times, surveillance is hidden and can be hard to discern, as is its very purpose and intention.

In any event, ubiquitous surveillance and preemption is one of the many reasons why Facebook can be problematic for serious political organising. Not only have social media corporations usurped the space for political discussions and organising in general, they’ve replaced it with a toxic mimic of community, which is really the largest and most powerful surveillance and propaganda network ever devised.22

Mobile Phone Interception

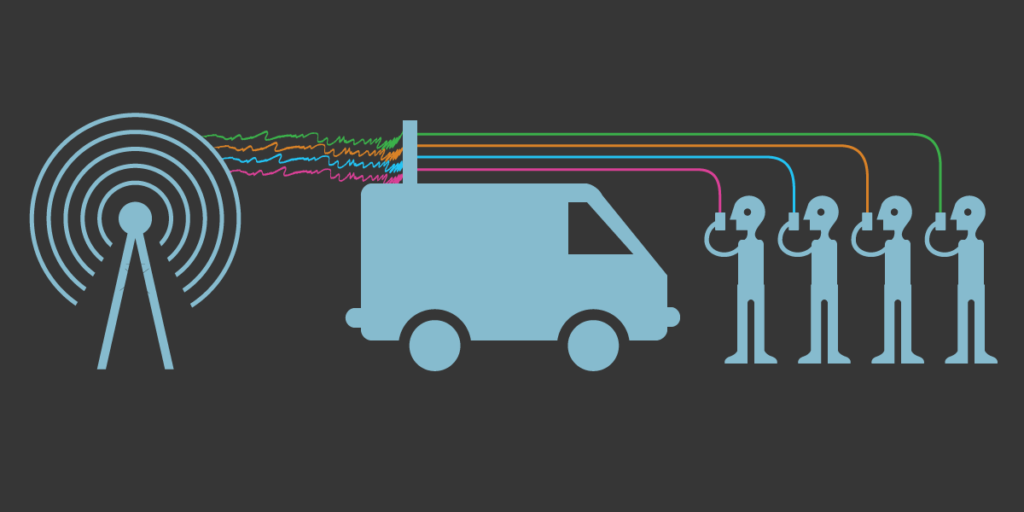

Mobile Phone Tower Simulators—also known as IMSI catchers, Stingrays, or ‘dirtboxes,’ are devices that masquerade as legitimate mobile phone towers, tricking a phone within a certain radius into connecting to the surveillance device rather than a real mobile phone tower. Police may use hardware like this to capture and identify all of the unique International Mobile Subscriber Identifiers (IMSIs) at a protest or other physical place. Once they’ve done that, they can use the phones’ IMSIs to try to identify the activists who own the phones.

This capability, along with other mass surveillance already deployed, such as the Federal Government’s Metadata Retention Scheme, means that identifying and following activists who are carrying a phone is relatively easy and little work,23 especially as all mobile phones are essentially tracking devices that just happen to make phone calls.24

Mobile Phone Interceptors can be mounted on vehicles, aeroplanes, helicopters and drones. There are also smaller handheld devices that have similar capabilities.25 In most cases, if you have a phone with you at a protest, you should assume it is being monitored, and that the police have the ability to potentially identify and track its owner. This occurs regardless of any encryption tools you may or may not be using on that device.

Police Operation Centres

Victoria Police chose New Year’s Eve 2016 to launch a new mass surveillance centre in Flinders Street which “channel[s] data 24 hours a day seven days a week from across Victoria Police, including the Air Wing, the State Police Operations Centre, State Control Centre and Police emergency communications centre”26 in order to respond quickly to ‘unplanned events or gatherings.’”27

Live feeds from CCTV cameras across Melbourne are fed into the centre, along with real-time monitoring of social media,28 which is analysed by police and “a dedicated team of science, technology, engineering and mathematical analysts to help police interpret data.”29

The centre is modelled on mass surveillance centres used by the New York Police Department in the United States, and was set up in Melbourne after the Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, visited New York in May 2016 to receive “high-level briefings from the NYPD’s Chief of Intelligence.”30

Surveillance centres such as these are used to monitor protest events as they occur throughout the city, but it would be just as important to emphasise the police’s stated aim of enacting mass surveillance technologies in the name of ‘preemption,’ quelling activity before it even occurs. Put in an activist context, centres like these can pose a concerning encroachment on political expression.

Resistance is not Futile

Overcoming a culture of surveillance and repression is difficult, but not impossible. The first step is being aware of what we’re up against. The next steps involve courage, resilience, smart strategy, commitment, and instituting and supporting strong support networks such as MALS that help activists and movements do their work. Digital security support, legal support, arrestee support, mental health support, medical support, fundraising and organising, transport, and feeding the ‘troops’ are all vital and interconnected parts of a culture of resistance that is working towards ending exploitation and subordination together.

In terms of surveillance, paranoia is a big one, as it’s debilitating, and a very easy way for opponents to destroy movements from the inside with very little work. All they have to do is instil a belief that police or private intelligence firms are omnipresent or omnipotent, so that you begin to self-censor, or fear inhibits or shuts down your work completely. Sure, those in power have all this fancy equipment and use it to target, intimidate, and harass our movements, but they’re not all-powerful or all-knowing. In a lot of cases, they’re a bungle of incompetence, just like most other social institutions made up of humans, and a belief in their espoused omnipotence only reinforces the image that they themselves spend millions of dollars per year projecting and perpetuating. A culture of fear and paranoia in activist movements only helps those in power.

Having said this, there are legitimate threats and serious risks. If you’re careless about technical surveillance and its real potential, you put yourself, others, and movements as a whole at risk of serious harm. At the end of the day, all good activist work involves a disciplined commitment to weighing up these threats thoughtfully and assessing risks on a case-by-case basis. For example, if your work involves protecting vulnerable people, what is the risk of harm to yourself and others by taking your mobile phone with you–that’s full of all your contacts–to a particular demonstration or rally? What would happen if the police searched or seized it? Or, if corporate spies infiltrated your movement right now, how easy would it be for them to access all of your documents? What are the risks and likelihoods in the context of all the elements of your activism, and how can you militate against each of them or minimise them?

These are the sorts of things we need to be talking about and working out together as serious resistance movements, especially as digital surveillance continues to escalate and expand into ever-more areas of everyday life, strengthening those in power.

Speculation, gossiping, and rumours are harmful. Knowing what we’re up against, with informed decision making is much better. This instead cultivates a culture of resistance that is smart, healthy, resilient, supportive, but above all–effective.

Sign up for our Digital Security Workshops

MALS runs training events throughout the year that focus on practical solutions to activist support. Our digital security workshops provide a technical support forum for conversations around Open Source tools and strategies to help protect activists and activist groups from increasingly intrusive digital surveillance by police and corporate spies. How do I encrypt my e-mail? Why is Facebook harmful for organising? How do the police use surveillance as a tool of repression and intimidation? How can we push back? Related topics include security culture in general, encrypted communications techniques, data awareness online and offline, privacy as a concept but also as a legal right, and specific anti-surveillance communication techniques and tools.

You can browse our schedule of upcoming events, or subscribe to our Newsletter, to learn more!