Interim report on public housing detention directions in Flemington and North Melbourne

Executive summary

The threat posed by Covid-19 has led to the mobilisation of state power and authority in new and untested ways. While the community has a shared interest in successfully containing the virus, early evidence suggests that enforcement of public health orders disproportionately impacts on oppressed, poor and marginalised communities.

In July 2020, the Victorian Government took unprecedented steps in an effort to contain Covid-19 in nine public housing towers in North Melbourne and Flemington, issuing detention orders that confined approximately 3000 residents to their units without notice. While many residents had long held concerns for their health and welcomed interventions to address risks associated with Covid-19, the unexpected and highly coercive nature of the intervention was a great source of distress for many. This was further compounded by significant shortcomings in the delivery of food and other essential supplies, antagonising behaviour towards community groups and residents and confusion and miscommunication on the ground.

The logistical challenge associated with an acute public health intervention of this nature is real and acknowledged. The government is required to grapple with unprecedented challenges that are complex and often require dramatic changes to the way services are provided. There is general goodwill and patience within the community for the extraordinary circumstances in which we find ourselves in, where care and respect is demonstrated in decision-making and the exercise of powers.

However, the problems with this intervention cannot easily be characterised as simple errors or missteps, but reflected fundamentally prejudiced assumptions about public housing residents. The extreme police presence (with 500 officers deployed across the towers) reflected an assumption of widespread non-compliance with health advice. The mistrust and obstruction of local organisations (often representing marginalised communities or staffed by people with direct experience of public housing) reflected an unwillingness to listen and learn from those with knowledge and expertise, which could have been leveraged to improve the service response. The confused and fragmented interventions demonstrated the government’s inexperience and inability to mount a culturally-informed, community-led and health-driven service response, instead falling back on command and control measures that act to frighten and punish. It became clear early on that this intervention was not designed with the dignity and rights of residents in mind. This report provides a high-level overview of issues and incidents observed by trained legal observers who were present at a range of public housing sites affected by detention directions. The issues we observed ranged from significant logistical shortcomings (limiting the ability of residents to access essential supplies or exercise basic rights) through to police intimidation and antagonism of residents and community groups alike. This report seeks to capture a high-level overview of the key issues observed. However, all incidents have been meticulously recorded and documented and further information can be provided on request.

Background

On 4 July 2020, the Deputy Chief Health Officer in Victoria authorised detention directions against nine public housing units in Flemington and North Melbourne.1 These orders restricted the circumstances in which residents could leave their homes and were made pursuant to the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 (the Act) in response to the risk posed by Covid-19.

The Victorian Premier announced the detention directions at a press conference that afternoon and confirmed that the ‘hard lockdown’ would come into effect immediately (at 3:30pm that same day).2 The Premier noted the intention is to limit the detention period to five days, subject to widespread testing and results, acknowledging that the orders are expressed to apply for 14 days. A heavy Victoria Police contingent was immediately deployed to the public housing towers to enforce the orders.

Residents received no forewarning of the detention directions and had no opportunity to prepare (such as make arrangements for food, supplies or medication) and were therefore wholly reliant on service providers to meet their needs. Early reports from residents filtering through social media and community organisations suggested that many residents were struggling to get basic supplies such as food, medication or other necessities and were distressed and confused about the orders. They also suggested that residents did not receive timely, official communication after the fact, and many found out about the immediately effective detention directions from social media, television, or word of mouth.

A range of community and other services quickly mobilised to support residents, particularly the Australian Muslim Social Services Agency (AMSSA). MALS joined local community legal centres (Inner City Legal Centre and Flemington Kensington Community Legal Centre) to monitor the implementation and enforcement of the detention directions. MALS was invited by local community members, as well as being asked to report any concerns to the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commision (VEOHRC) under the United Nations Nelson Mandela Rules on detention of peoples.

On 9 July, the media was advised that based on testing outcomes, residents of two towers could move to Stage 3 ‘Stay at home’ restrictions from 5pm that day and a further six towers could do the same at 11.59pm that night. Due to a high number of positive cases, all residents of one tower (33 Alfred Street North Melbourne) would be treated as close contacts of positive cases and would be required to self-isolate for 14 days.

MALS was focused on observing interactions between police and residents, food and supply deliveries and, in the case of the final tower (33 Alfred St), supervised exercise. Trained observers were present to record and monitor interactions and this forms the basis of this report.

Key issues and concerns

Obstruction of community relief efforts

Concerns include lack of recognition of AMSSA as legitimate community organisers with skills, knowledge and expertise on the needs of locked-down residents as well as inappropriate behaviour of DHHS and VicPol staff towards AMSSA volunteers.

As noted above, a range of community services mobilised to provide food and other supports to residents in the nine towers. The most prominent was AMSSA, which offered its support and services to all residents (regardless of cultural or religious background), and had strong links to residents in the towers. This was not leveraged by DHHS or Victoria Police and instead AMSSA was obstructed and hindered in its attempts to provide food, essential items and support.

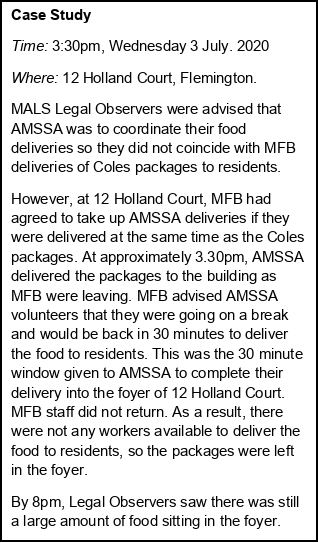

Misdirection and confusion around processes to food delivery led to a range of problems. AMSSA was often provided with incorrect information about when and how to deliver food for it to be taken to residents’ doors, which was often done by the Melbourne Fire Brigade or the State Emergency Service. This led to AMSSA deliveries not being made in a timely manner (or at all), increased health risks and potential cross-contamination (where residents came down to try and retrieve food for themselves downstairs) and food wastage (due to food sitting unrefrigerated for long periods).

The lack of recognition of AMSSA as suppliers of legitimate food relief from officials on site also contributed to an altercation which led to one AMSSA volunteer being arrested on the evening of Tuesday 7 July. It also required constant (and tiresome) negotiations and led to frustration for residents.

As the days went by and after ongoing negotiations with police and DHHS continued, AMSSA’s food and supply deliveries had become more accepted by officials on the ground. On Thursday 9 July, only one day after AMSSA volunteers had difficulty delivering food to residents, the Minister for Police and Emergency Services, the Hon Lisa Neville MP, thanked AMSSA for the food relief they were providing, stating that AMSSA would become an official food aid group working with DHHS going forward.

Culturally inappropriate supplies

Concerns include DHHS delivery of non-halal meat, and a lack of understanding about the practical effect of this on locked-down residents who were wholly reliant on these deliveries.

MALS observers witnessed food donations made by mainstream service providers contained food items that could not be consumed by a number of residents for religious or cultural reasons. There did not appear to be any effort to be mindful in common dietary requirements for residents and this had the practical effect not only of causing distress and offense, but also limiting the food that residents could eat.

On the fifth day of detention on 8 July (when residents’ common dietary requirements should have been reasonably clear) MALS witnessed food packages that contained non-halal meat. AMSSA requested this meat be removed from packs and that AMSSA food items be delivered along side the donated food pack. The MFB Commander was not willing to take the meat out, saying that it would take too much time. He suggested that residents discard any non-halal meat in their food package. AMSSA volunteers responded that this would be disrespectful to the residents.

Officials from DHHS and the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) negotiated with AMSSA volunteers and MFB. MFB agreed to deliver AMSSA food and donated food packages, and take out non-halal meats. However, by this point, the community members were agitated, and non-halal meats had already been delivered to the first floor of one of the towers.

Obstruction of legal observers

Concerns include obstruction and intimidation of legal observers attending sites.

MALS observers satisfy lawful exceptions to Stage 3 ‘Stay at home’ orders, as they are conducting (volunteer) work, which cannot be done from home. MALS was mindful to field modest teams who wore masks, practiced good hand hygiene and maintained physical distancing wherever possible.

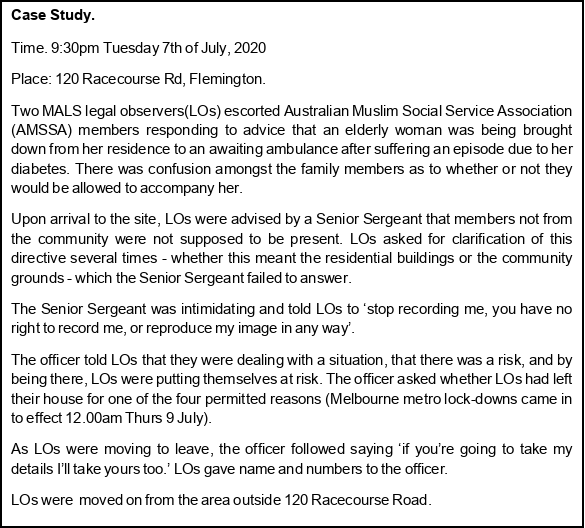

Notwithstanding this, observers reported incidents of intimidation of legal observers. On 7 July (at 120 Racecourse Road, Flemington) a police officer advised observers they could not be present due to Stage 3 restrictions. When observers sought clarification and explained their reasons for lawful attendance, a senior officer began to intimidate observers and deny their ability to record interactions (the name of the officer can be provided on request). The legal observers complied with a move-on order from police. On 10 July, legal observers were denied entry to the grounds of 33 Alfred St without clear explanation of why (beyond the lock-down of the site). They were threatened with fines if they returned to the site.

Conflicting advice on command chain of locked-down towers

Concerns include consistent inability or unwillingness to articulate chain of command and key decision-makers when requested, causing confusing and undermining accountability.

At every attendance, it is standard practice for MALS observers to establish the chain of command and individuals responsible for decision-making on-site. This enables observers to advise of their attendance, describe MALS’ role and establish the pathway to escalate any observed concerns.

MALS observers commonly received unclear or conflicting information about the chain of command. Some observers were simply unable to obtain this information (either because it was not known or because people on site did not want to disclose it) or were given conflicting information about this (sometimes being told it was DHHS, other times being told it was Victoria Police). AMSSA also received this type of conflicting or confusing information when it sought to negotiate deliveries or other matters.

This not only hindered operational supports and supplies for residents, but also undermined transparency and accountability on the ground, as there was no pathway to effectively escalate issues or concerns.

Unjustified and disproportionate police presence and other punitive measures

Concerns include the use of police in a public health response and excessively punitive measures to control residents.

MALS consistently observed a significant police presence surrounding each of the towers, particularly in the early stages of the lockdown.This presence was immediate, before there was any evidence of widespread non-compliance or unlawful behaviour from residents and constituted a unjustifiably punitive response to a public health issue. It was also a source of significant stress for a number of residents, particularly given the fraught history of over-policing and discriminatory practices against these specific communities.

This included a significant police presence remaining at each estate after the ‘hard lock-down’ was eased to Stage 3 restrictions at 11:59pm, Thursday 9 July. MALS observers were advised by police on Thursday 9 July that Victoria Police would maintain their presence in order to impose Stage 3 restrictions and had been instructed not to interfere with residents’ permitted activities ‘unless a fight broke out’. This model of proactive policing is incompatible with the notions of public safety and health, and seriously undermines the residents’ rights. MALS observed this heavy policing during the night of, and the day following the restrictions ease, despite the estates now being under the same restrictions as the rest of Metropolitan Melbourne. This further demonstrates the intimidating and punitive measures police exercise against marginalised communities.

There were a range of other responses that were unnecessarily punitive and pre-supposed unlawful behaviour. This included care packages prepared by community organisations or family members being searched by police for ‘contraband’ and cyclone fencing being installed to create an ‘exercise yard’ for residents undertaking supervised exercise at 33 Alfred St (this was disassembled following negotiations). These contributed to a feeling of discrimination, punishment and disproportionate control of residents.

MALS also notes the concerning use of the Public Order Response Team (PORT). PORT police members are drawn from general duties who have been provided with specialist crowd control training. PORT is designed to provide a rapid and ‘force-of-numbers’ response to public order incidents and has dedicated vehicles and riot control equipment. MALS legal observers saw numerous PORT vehicles in and around the estates, providing support to the policing operation.

Lack of supervised exercise and fresh air for residents locked down in 33 Alfred St

Concerns include a lack of clarity around supervised exercise arrangements, delays in offering exercise to residents and unnecessarily punitive supervision.

As noted above, the residents of 33 Alfred St were required to act as close contacts of a positive case due to high infection rates, requiring 14 days of self-isolation. DHHS advised residents of the availability of supervised exercise downstairs by agreed appointment. There were some delays and confusion about its availability and it appeared to be very limited (somewhere between 15 and 30 minutes) with a strong police and DHHS presence.

Although DHHS and Police advised MALS legal observers that people were able to access fresh air and exercise, legal observers only saw 5 residents people on Sunday 12 July 2020. Although MALS concedes that legal observers may have not physically seen all fresh air and exercise, MALS fielded a team from approximately 9:30am until 6:45pm on Sunday and were monitoring the site almost constantly. The fact that legal observers only saw 5 people for the entire day indicates to MALS that access to fresh air and exercise was not widely available as legal observers were led to believe.

About Melbourne Activist Legal Support

Melbourne Activist Legal Support (MALS) is an independent volunteer group of lawyers, human rights advocates, law students and para-legals. MALS trains and fields Legal Observer Teams at protest events, monitors and reports on public order policing, provides training and advice to activist groups on legal support structures and develops and distributes legal resources for protest movements. MALS works in conjunction with law firms, community legal centres and a range of local, national and international human rights agencies. We stand up for civil and political rights.

This report is a public document and is provided to media, Victoria Police Professional Standards Command (PSC), Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC), Government ministers, Members of Parliament and other agencies upon request.

A downloadable copy of this Statement is available here (PDF).

For inquiries regarding this statement please contact: m[email protected]