Statement of Concern: Policing of Free Palestine March, 4 February 2024

Melbourne Activist Legal Support (MALS) expresses concern regarding the violent and unsafe policing of protesters and legal observers at the Free Palestine march in the Melbourne CBD on Sunday 4 February, 2024.

Melbourne Activist Legal Support (MALS) fielded a team of six (6) trained legal observers at this Free Palestine protest that took place at the State Library on Swanston Street in the Melbourne CBD.

The protest was organised by Free Palestine Melbourne. Event promotions emphasised the anti-racist nature of the event and its opposition to antisemitism and Islamophobia. The event was promoted with a start time of 12pm with speakers addressing the crowd at the State Library. Due to the high temperatures expected on the day protest organisers, with the assistance of medics and marshals, planned a short march route along Swanston, Lonsdale, Russell and La Trobe streets, before returning to the State Library.

Legal observers worked in two groups of three from 12:00pm until 2:40pm, monitoring and documenting observed police manoeuvres, conduct and interactions with protesters. The team observed approximately 20 police officers in attendance from different police units including general duties officers on foot and bicycle, Public Order Response Team (PORT) officers, highway patrol unit, and plain clothes detectives. Legal observers also noted the presence of at least two large police buses and at least two divisional vans. Legal observers noted approximately 15 additional PORT officers in attendance in the State Library precinct when the march returned to the State Library at approximately 1:40pm. Between 1:40pm and 2:30pm legal observers witnessed one arrest and numerous incidents of the use of physical force against protesters as well as legal observers.

During that time, the legal observer team noted areas of concern. Five recommendations to authorities are included at the end.

Summary

In consideration of the high temperatures on the day, protest organisers and medics planned a short march that started and ended at the State Library. A relatively low number of police officers were in attendance, with police resources concentrated mainly on traffic control during the march.

The protest was safe and peaceful, including when the march returned to the State Library and a group of protesters gathered on Swanston Street in front of Melbourne Central shopping centre. However, police decisions regarding the arrest of an independent photo-journalist appeared to greatly escalate tensions between police and protesters. The combination of the violent arrest of this person who had clearly expressed to police their mental and physical discomfort and police’s aggressive crowd control tactics directly contributed to creating a dangerous environment which placed people’s safety at risk.

The arrest was allegedly instigated by an act of stickering ( placing an adhesive sticker on a surface). Legal observers also noted that police officers witnessed someone else stickering during the march and did not respond at all. MALS notes that police could have chosen to exercise the same discretion in this instance but instead chose to pursue the person, an act which was likely to agitate the protesters present and could not reasonably be argued as being in the public’s interest.

The policing observed at this protest is consistent with a pattern of policing witnessed at several recent protests. The lack of accountability or consequences for those police officers who engage in misconduct, and with no obvious changes to policing operations, is directly contributing to police creating dangerous, unsafe environments for people who are acting well within their rights to participate in peaceful protests.

Police use of force against protesters

Legal observers witnessed and recorded multiple instances of police grabbing, shoving, pushing, and using offensive language towards protestors. Many of these use of force incidents appeared to be forceful, intimidating and dangerous.

At approximately 1:40pm on Swanston Street in front of Melbourne Central shopping centre, legal observers witnessed a person surrounded by five police officers. The crowd of protesters then gathered in front of them and started chanting, “Let him go! Let him go!

At approximately 1:43pm, around 10 general duties and PORT officers formed a line between the person and police officers and the crowd of protesters. The police officers speaking to the person then arrested them by violently grabbing the person’s arms and twisting them behind their back and pushing them front-on into the wall of the building. One police officer put both their arms around the person’s neck in an attempt to grab the person’s phone along with two other officers (see Figures 1-2). Legal observers heard the person say they were “not okay” and tell police they had a connective tissue disorder which made it very painful to have their arms restrained.

Figures 1-2: Police officers attempting to grab the arrestee’s phone (arrestee face blurred).

At this time, legal observers witnessed general duties police and PORT officers grabbing, shoving, and pushing protesters and protest marshals. Police were observed aggressively pushing people off the footpath, grabbing people roughly on the arms, and yelling loudly at them as the arrestee was led away.

As police formed a circle surrounding the arrestee and started to lead them towards La Trobe Street, legal observers noted that a protester was caught inside this circle of officers and was being pushed along the footpath in front of the arrestee. Legal observers witnessed two police and one detective roughly grab this protester by each arm, pull them out of the police circle, shove them to the side of the footpath, and then release them once the police and arrestee had moved past them (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Three police officers restraining a protester who had been caught inside a police circle.

Approximately 15 general duties and PORT officers then positioned themselves to form a line between marshalls and protesters and the arrestee as they were being led towards La Trobe Street.

Figures 4-5 Police officers twisting a person’s arms behind their back (arrestee face blurred).

Legal observers also witnessed PORT officers putting on rubber gloves and protective goggles, which prompted marshals to advise protesters to also put on protective goggles if they had them.

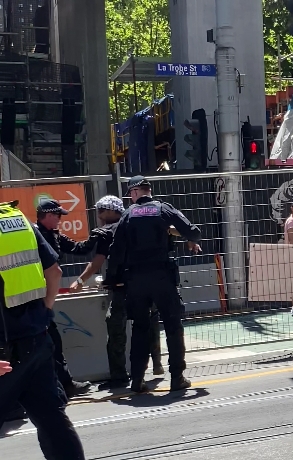

At approximately 1:47pm on La Trobe Street as the crowd of protesters followed where the arrestee was being taken, PORT officers were observed grabbing a flag out of an individual protester’s hand and aggressively pushing them away before handing the flag back to them (see Figures 6,7,8).

Figures 6, 7, 8: PORT officers on La Trobe Street grabbing a protester’s flag out of their hand and pushing them towards Swanston Street.

At approximately 2:13pm, protest marshals informed legal observers that the arrestee was receiving medical care in an ambulance on the corner of La Trobe Street and Elizabeth Street. Legal observers made their way to the location arriving at approximately 2:14pm. At approximately 2:31pm, the person exited the ambulance and attended to their personal belongings. At approximately 2:33pm, police formally issued the person with a move-on order and informed them they could not return to the CBD area for 24 hours.

MALS believes that the police’s overly forceful crowd control measures were unnecessary under the circumstances as the protest was contained and safe at the time. Rather than making decisions based on the public interest, police actions served to increase tension, fear, and anger amongst the crowd of noisy but peaceful protesters.

Commentary:

The right to freedom of assembly is protected under the Australian Constitution, Victoria’s Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“Every person has the right of peaceful assembly.” (State Government of Victoria 2006:2)

“The right of peaceful assembly shall be recognized. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed inconformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.” (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Article 21)

“Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.” (United Nations, Article 20)

These mechanisms provide protection for people exercising their right to peaceful protest as a legitimate tool of political expression.

It is formally recognised that peaceful protest is disruptive in nature and includes actions such as noisy disruptions, directing actions towards an identified target, and occupations of public places such as roads and footpaths. In United Nations Human Rights Committee General comment No. 37 (2020), peaceful protest is recognised as:

“… peaceful assemblies wherever they take place: outdoors, indoors and online; in public and private spaces; or a combination thereof. Such assemblies may take many forms, including demonstrations, protests, meetings, processions, rallies, sit-ins, candlelit vigils and flash mobs. They are protected under article 21 whether they are stationary, such as pickets, or mobile, such as processions or marches.” (United Nations 2020:para. 6)

“Their scale or nature can cause disruption, for example of vehicular or pedestrian movement or economic activity. These consequences, whether intended or unintended, do not call into question the protection such assemblies enjoy.” (United Nations 2020:para. 7)

It is also recognised that protesters should not be restricted access to the target audience of their protest: “… given the typically expressive nature of assemblies, participants must as far as possible be enabled to conduct assemblies within sight and sound of their target audience.” (United Nations 2020, para. 22)

Regarding the use of force by police, the Victoria Police Manual (VPM) states that:

“… the goal of policing activities is to minimise harm caused by the actions of police or the actions of others. This is a broader concept that extends beyond the use of force and physical injury. It encompasses human rights, psychological and emotional harm and other impacts on community safety and confidence.” (Chief Commissioner of Police, n.d., Operational safety and the use of force)

Under sections 462A and 463B the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) police may use force to prevent serious offences from taking place, during an arrest, or to prevent a suicide. Any use of force must be reasonable, necessary, proportionate to the threat faced, and in accordance with legal requirements found in legislation, the common law, and the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities (Human Rights Law Centre 2011:7). As such, any use of force used by police with the aim of restricting people from exercising their right to protest may constitute excessive use of force.

In a broader sense, everyone has the right to be treated with dignity and respect, to freely socialise in public, and to express themselves freely. Human rights standards identified in the VPM require police to act compatibility with human rights under section 38 of the Human Rights and Responsibilities Charter Act 2006, and prohibit police officers from unreasonably or disproportionately impeding these fundamental human rights through acts of harassment, abuse, or physical violence (Chief Commissioner of Police, n.d., Human rights standards).

MALS is concerned by the use of excessive, unreasonable, disproportionate, or unnecessary force against people who are exercising their right to protest. Any Police use of force against members of the public escalates conflict and tension and creates dangerous situations in which public safety is put at risk. In the longer term, these police actions can damage society’s democratic foundations, repress people’s civil and political rights, and significantly reduce the space within which the public has to assert their political voice.

Use of force and obstruction of legal observers

MALS legal observers encountered obstruction by police when attempting to identify and make contact with the Forward Commanders before the protest began. When legal observers approached a group of six police officers at approximately 11:50 am, police officers were not particularly forthcoming with information about Forward Commanders, and instead attempted to interrupt the legal observers’ line of questioning to shift the conversation to allow police to record the legal observers’ details.

After the legal observers recorded the details of one Forward Commander, police advised them that another officer was also acting as Forward Commander and directed the legal observers to where they could be found. At approximately 11:55 am at the southern end of the tram stop on Swanson Street, legal observers approached the police officer who had been identified as a Forward Commander. While this officer was speaking on their phone, legal observers attempted to photograph their ID badge from a safe and respectful distance so as not to interrupt their phone conversation. However, the officer repeatedly moved their body and positioned their hands in such a way as to prevent legal observers from seeing and photographing their ID badge. While attempting to view and photograph their ID badge, another police officer pushed a legal observer and told them to move away while the Forward Commander was on the phone. This officer then confirmed their own details as well as the Forward Commander’s details. As the Forward Commander’s phone conversation continued, legal observers were not able to introduce themselves to explain the role of legal observers. These obstructive police actions effectively stopped the legal observer team from explaining the role of legal observers to the Forward Commanders and asserting their right to fulfil this role before the rally began.

Towards the end of the rally, five of the six legal observers present reported being grabbed, shoved, pushed, and yelled at on separate occasions while they were monitoring and documenting the arrest. MALS emphasises that legal observers did not hinder or obstruct police actions in any way at any time.

At approximately 1:42 pm on Swanston Street in front of the entrance to Melbourne Central shopping centre, three legal observers reported that a Senior Sergeant repeatedly and aggressively pushed them and attempted to cover their camera while they were filming an arrest (see Figures 10-11).

Figure 10-11: Senior Sergeant blocking a legal observer’s camera to stop them filming an arrest.

Further, one legal observer reports that the same Senior Sergeant grabbed and squeezed their arm very tightly in order to move them and yelled loudly at them, “Get out of my fucking way”. When the legal observer asked the officer not to touch them, the officer replied, “Don’t tell me what to do”. When the legal observer moved, another officer said to them, “Don’t get in my way, don’t hinder police” (see Figure 12). Footage of this incident shows that legal observers did not hinder or obstruct police in any way.

Legal observers also report that police officers refused to answer their inquiries about which police station the arrestee was being taken to. As a result of the officers failing to provide this information, the legal observer followed and asked for this information as the arrestee was being placed in a divisional van on La Trobe Street. The legal observer moved to a clear and open space at the end of Swanston Street to film the police walking the arrestee towards the divisional van. This position allowed the legal observer to capture footage of police twisting the arrestee’s arms behind their back in unnatural positions. An arresting officer yelled at the legal observer to move; however, when the legal observer attempted to move, they were caught amongst the crowd of general duties police and PORT officers who were following the arrest, and then caught behind these officers as they started to form a line between the divisional van and protesters. These officers repeatedly and aggressively yelled at the legal observer to move. Footage of this incident shows the legal observer saying to police, “I don’t know where to move, there’s nowhere to move”. The legal observer then moved as far out of the way of police as possible by standing with their back against the divisional van (see Figure 13). Once police had established their line, the legal observer was eventually able to make their way out from behind the police line and join other legal observers who were filming the incident from within the crowd of protesters.

Commentary:

Any obstruction of, or use of force against, legal observers is unacceptable.

When legal observers cannot make direct contact with on-site Forward Commanders, their ability to relay concerns promptly and directly to appropriate police members is hindered. Establishing a direct communication link with the officer in charge at protest events is an essential element of the legal observer role and, as such, should be facilitated by the police officers present.

Independent monitoring of the policing of protests is essential for defending the right to organise and participate in public assemblies. The practice of independent scrutiny of police powers is recognised by the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC). The UNHRC describes monitoring as necessary for the exercise of the right to peaceful assembly, and emphasises the responsibility of law enforcement officials to “[protect] journalists, monitors and observers” (United Nations 2020:para. 74).

Legal observers have the right to observe, monitor, and document police actions at protests and other actions without obstruction, including being allowed access to locations and spaces where they can clearly observe police actions:

“… [observers] may not be prohibited from, or unduly limited in, exercising these functions, including with respect to monitoring the actions of law enforcement officials. They must not face reprisals or other harassment, and their equipment must not be confiscated or damaged. Even if an assembly is declared unlawful or is dispersed, that does not terminate the right to monitor” (United Nations 2020, para. 30)

Although legal observers position themselves so as to secure satisfactory vantage points to film police actions, they do not hinder, obstruct, or otherwise interfere with any police actions. The reason why legal observers have the right to observe police actions so is evidenced in the footage captured by legal observers of police using force against members of the public, against protesters, and against the legal observers themselves- these are exactly the types of police actions that make it necessary for legal observers to monitor police operations in order to identify potential human rights abuses.

MALS is greatly troubled that several police officers used excessive physical force against legal observers. The obstructive actions and use of force by a Senior Sergeant against legal observers is particularly concerning as senior officers are responsible for setting a behavioural standard for subordinate officers. When police officers in leadership positions conduct themselves in a manner that constitutes misconduct in breach of the VPM, this serves as a negative model of practice for other officers and contributes to the establishment and perpetuation of an operational culture of unlawfulness.

MALS has previously raised concerns about police mistreatment of legal observers with the Chief Commissioner of Victorian Police and the Victorian Human Rights Commissioner, and once again asserts that any use of force against legal observers is entirely unacceptable.

Dangerous and aggressive crowd control operations

Legal observers witnessed general duties officers and PORT officers conducting dangerous and aggressive crowd management tactics which put people’s safety at risk.

At approximately 1:40pm on Swanston Street in front of the entrance to Melbourne Central shopping centre, protesters gathered in front of police as they were arresting someone and started loudly chanting, “Let him go”. At this point, several general duties and PORT officers appeared and positioned themselves in front of the protesters. As police officers violently arrested the person and began walking them towards La Trobe Street, protesters continued to chant and walked along Swanston Street following the police as they took the arrestee away. Police control of the situation and the formation of police lines appeared chaotic and haphazard. Furthermore, police directions to protesters were inconsistent, leading to general confusion about where people and police were moving to. In some instances, police moved people towards a specific area on La Trobe Street, only for them to be immediately directed to move away from that area by other officers.

At approximately 1:47pm, the arrestee was placed in a divisional van, which then drove westbound down La Trobe Street. Legal observers noted that the van continued to drive down La Trobe Street even as protesters spilled onto the road around it (see Figure 14). After the van had passed, approximately 30 police and general duties officers moved to La Trobe Street to move protesters off the road.

The continually moving and changing area-denial lines resulted in escalating physical contact between police officers and people who either were trying to get out of the way, people who wanted to remain in a particular location, or people who could not move easily due to the chaotic crowd situation. These police manoeuvres and the accompanying police use of force resulted in immense anger, confusion, and distress. These police actions resulted in a chaotic and dangerous situation for everyone. Many of these manoeuvres and the way they were conducted involved high levels of physical force toward people including pushing, grabbing, and shoving.

Commentary:

Police lines that are unclear or unplanned can substantially escalate confusion and conflict and increase the risk of excessive use of force resulting in injury.

MALS believes that several area-denial manoeuvres observed at the protest were unnecessary, dangerous, and failed to adequately consider the human rights of the people present. At numerous points of their operation, police failed to de-escalate high-tense situations and unnecessarily obstructed people’s movement. At other times, police failed to act to ensure the public’s safety.

MALS has observed similar unplanned, chaotic, and dangerous manoeuvres by Victoria Police at several recent protests. Police tactical decisions at protests can have significant and negative consequences, can unnecessarily generate fear, stress, and tensions and create unnecessary risks to safety, and increase the likelihood of arrests and use of force.

Police not wearing identification badges and refusing to provide name and details

Throughout the course of the day, MALS legal observers noted that several police officers including detectives were not wearing identification (ID) badges. Legal observers also witnessed several of these officers place their hands and equipment in such a way as to prevent them taking photographs as evidence of their lack of ID badge. These evasive actions indicate that those police officers are aware that they must wear an ID badge and were attempting to hide the fact they didn’t have one.

At approximately 1:40pm on Swanston Street in front of Melbourne Central shopping centre, legal observers witnessed several police officers walking behind and alongside someone attempting to stop them. During the conversation that followed, the person was heard to give a name and address to the police. However, when they repeatedly asked the police officers to provide their names, they refused to do so, indicating that they couldn’t hear the person’s questions. Legal observers noted that none of the five police officers who were surrounding the person gave their name or details when asked.

Commentary:

Uniform and appearance standards outlined in the VPM confirm when police officers must wear an ID badge:

“Members in uniform are required to wear current issue name tags.” (Chief Commissioner of Police, n.d., Uniform and Appearance Standards)

“Members may be authorised to wear tags that detail only their registered number under local or temporary arrangements relating to planned operations, or as a management option relating to planned operations, or as a management option relating to THASM (Threats Against Serving Members) files…

- where possible, there should be consistent usage within a group of either name or numbered tags

- use of numbered tags should be detailed in operation orders in ‘dress of the day’ and communicated clearly through other operation tools, including joining instructions

- wearing a numbered tag does not relieve any member of their responsibility when requested to state their name, rank and place of duty (orally or in writing under s.456AA(4), Crimes Act, or any other legislative or customer service requirements.” (Chief Commissioner of Police, n.d., Uniform and Appearance Standards)

Police can ask for your name and address if they have a reasonable suspicion you have committed or are about to commit an offence, or if you might be able to assist their investigations into an indictable offense (Fitzroy Legal Service n.d.). If police ask for your name and address, you have the right to ask for their name, rank, and police station, and you can ask for these details to be provided in writing; if police refuse to give you these details they can be fined (Victoria Legal Aid 2024).

When police cannot be identified it becomes extremely difficult for members of the public to pursue justice in instances of police misconduct. This has implications for police accountability and potentially creates an environment where police misconduct is enabled by creating a situation where officers can evade responsibility.

Further, the inability to identify individual police officers can contribute to eroding people’s trust in the police, damaging the relationship between police and protesters, and a lack of confidence in the polices’ ability to protect people’s rights.

ACTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In light of the above areas of concern, MALS calls upon Victoria Police and all authorities to ensure that:

- As a bare minimum, Victoria Police take proactive measures to ensure that officers comply with laws and policies governing the use of force at public assemblies.

- Victoria Police consult with bodies such as the VEOHRC to review its Victoria Police Manual (VPM) policies, police attendance at events and incidents, operational planning, and operation orders in relation to all large civil disobedience protest events in order to ensure that the rights to peaceful assembly, association and expression are not limited by operational tactics.

- Victoria Police provide clear directives to members and reinforce Operational Safety and Tactics Training (OSTT) regulations and training requirements to prevent further unlawful use of force against citizens involved in peaceful forms of protest activities.

- Victoria Police specifically include the role of civilian legal and human rights observers within the Victoria Police Manual Crowd Control Guidelines (VPMG) and Forward Commanders brief operational members of the requirement to ensure the safety and access of legal observers who may be present at protest events.

- Victoria Police ensure that all police officers, including detectives, are clearly identifiable to members of the public when attending events, including wearing identification badges as required in the VPM as well as instructed to provide their name and station when lawfully required to provide it.

________

Policy Rules contained in the Victorian Police Manual (VPM) cited above are mandatory and provide the minimum standards that employees must apply. Non-compliance with or a departure from a Policy Rule may be subject to management or disciplinary action.

________

This Statement of Concern is a public document and is provided to media, Victoria Police Professional Standards Command (PSC), Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC), the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC), Government ministers, Members of Parliament, and other agencies upon request.

For inquiries regarding this statement please contact: [email protected]