A Tale of Two Cities

One pandemic. Two ways of policing protests.

May 1 is International Workers’ Day, a day to demand fairer labour conditions and show solidarity across labour movements. Despite the pandemic, workers rallied around the world this May 1. Given the precarious economic times, gatherings in support of workers’ rights were likely all-the-more important this year.

Although both Victoria and New South Wales continue to be ‘under lockdown,’ demonstrators in Melbourne and Sydney went ahead with actions to mark the day.

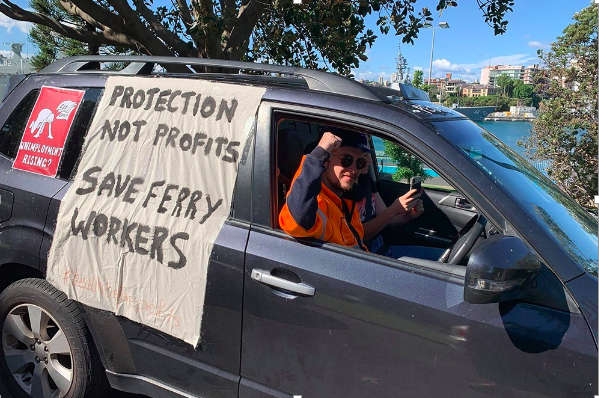

In Sydney, more than 200 demonstrators turned out in cars and on bikes. MALS understands that the NSW Police called organisers multiple times in the days beforehand regarding the legality of the protest and their intention to enforce public health directions. However, following negotiation, NSW Police stated they would enforce traffic violations or violations of social distancing. At the time of writing, one outlet reported that no infringement fines were issued.

In Melbourne, approximately twenty demonstrators gathered at the Eight Hour Day Monument and started walking into the Melbourne CBD along the street. Most demonstrators were wearing masks and video taken of the event indicates they were separated as they walked. about 20 metres down the street, the protesters were directed to the sidewalk by small contingent of police.

An officer is heard to say:

I need to have you all together, I need to give you a direction. At the moment there are no organised gatherings as part of the Chief Health Officer’s Directions under COVID-19. I’m not saying it isn’t peaceful, and I’m not saying you’re doing anything that isn’t peaceful, however the direction from the Chief Health Officer is that there is no organised gatherings of any kind. So what I’m going to ask you to do is to disperse from the group and we will have no further action…if the gathering is to stay together, you will be asked by police for your names and addresses and you will be issued an infringement under the directions of the Chief Health Officer.

The demonstrators complied and no fines were issued. Yet, despite the calm dispersal, the question arises: how was this different from the cavalcade in Sydney? While the march itself was ‘organised,’ was twenty demonstrators walking safely apart from each other putting themselves or the general public at greater danger than, say, Sunday afternoon at the grocery store?

The policing of the two protests appears to be a repeat of actions over the Easter period that took place in Melbourne and Sydney.

On 9 April, more than 60 vehicles joined a car cavalcade in Sydney demanding a living wage for all workers in the Federal Government’s COVID-19 stimulus package. The cavalcade encircled the NSW Parliament “several times” but attracted little to no police attention.

On 10 April, a cavalcade encircling the Mantra Hotel in Preston, outside of Melbourne, consisted of fewer than half the number of vehicles in Sydney and protesters were following social distancing requirements. Protesting the detention of asylum seekers held in the hotel under unsafe conditions in COVID-19, 26 of the protesters received infringement fines of $1652, totalling to more than $42,000 of fines. One of the organisers was arrested before the protest, held in custody for nine hours, charged with incitement, and had his phone, work computer, and the computer of his 15 year old son seized by police.

Clearly the approach to policing protests in COVID differs between Melbourne and Sydney. But why?

New South Wales and Victoria each have their own public health directives in place; each are written similarly:

- Both restrict freedom of movement (in both NSW and Victoria, Part 2, clause 5).

- Both restrict public gatherings (in NSW Part 3; in Victoria, Part 4).

- Both permit attending voluntary work (in New South Wales, clause 5(2)(b) and definition of ‘work’ at clause 3; in Victoria, clause 8(1)(a)).

One potential difference is that NSW directives provide broadly that “emergencies or compassionate reasons” constitute a “reasonable excuse” for leaving one’s residence (Schedule 1, clause 16). Protesting inhumane or unfair conditions could be argued to be compassionate reasons. In Victoria, “other compassionate reasons” for leaving one’s residence is more explicitly defined and largely relates to providing care, attending family services, giving blood, and escaping violent circumstances (clause 7).

In practice, the difference means little when both states’ directives are general. Written to protect public health in a time of unprecedented emergency, neither directive covers all circumstances. Thus, in the absence of law, there is discretion.

The discretion left to the Victorian and New South Wales police means that it is for the police to interpret whether a particular action constitutes a breach of the emergency directives. In doing so, they have broadly two options: to enforce the directives in a manner that aligns closest with the law’s public health purpose or its plain language.

The two different approaches seen in Victoria and New South Wales suggest this cleavage: policing of protest in NSW appears to permit protest while maintaining public health; restrictions and infringement notices in protests in Victoria appears to enforce the restrictions against ‘public gatherings’ without considering the context in which the actions occur.

Under human rights law, the right to protest, derived from the right to free expression and free peaceful assembly, can be reasonably curtailed in emergencies. But that curtailment must relate to the emergency at hand—in other words, if a protest is restricted because it would contribute to the spread of COVID-19, that might constitute a legitimate restriction. That way, the benefit of the doubt is for the protest—if the protest can proceed safely, it should be able to do so.

Although there is talk of ‘lifting the lockdown,’ Sydney and Melbourne are likely to remain under some form of restrictions for some time. The question is whether the policing of these restrictions—is for protecting public health or enforcing some form of police-defined public order.

By Jen Keene-McCann

Melbourne Activist Legal Support